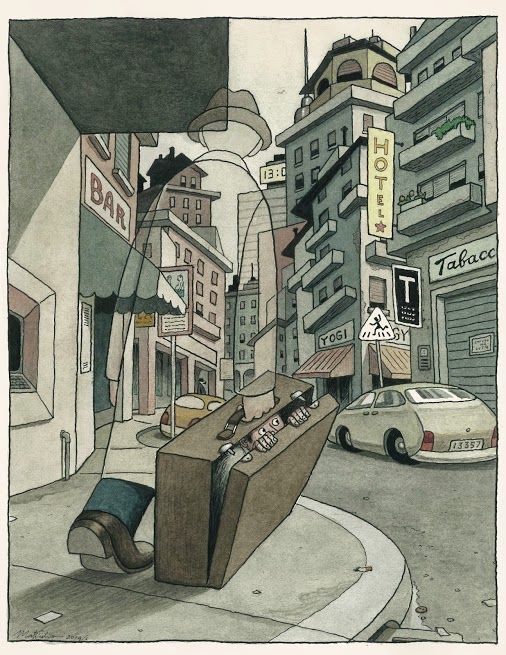

The poster looked new.

“Found. One Teddy Bear. Good condition. Obviously loved. Found on the bus stop seat at Sandells Road, about 8pm on the 25th.”

There was a phone number.

The poster didn’t say, “Come and get her.” That was implied.

This wasn’t my bear. My bear was safe and warm at home.

I didn’t like to think of a bear without a home; without the person who loved her.

I walked past that poster again the next day, and someone had written, “Paddington, come home,” in pencil. Who carries a pencil these days? They probably thought it was funny, and I guess it was, but there was still a bear without a home, and if it was anything like my bear, it couldn’t tell its saviour where its home was.

The next day, the poster had come undone on the bottom left corner. I pushed it back into place.

The day after that, it rained, and the poster got wet.

How do you tell if a search has a happy ending?

I asked my mum if she would ring the number.

“And say what, exactly?” My mum is a practical person. She gets to the point.

“Ask them if anyone has claimed the bear, of course.”

“Why don’t you ring them?” said my mum.

I knew she would ask that, and I had rehearsed my answer standing in front of my mirror. I do that sometimes.

“Because I don’t know who will be on the other end of the phone, and if it’s a grown-up, then grown-ups take other grown-ups seriously. You might get a straight answer.”

It looked and sounded convincing when I did it in front of the mirror.

“Okay,” was all she said.

The poster was illegible that next day.

When I got home, I tried to look as though I hadn’t been thinking all day about the result of my mother’s phone call.

“I’ll ring around lunchtime,” my mother had said, “it’s a civilized time to ring someone.”

I thought, what if she/he is at work, school, or off scuba diving, but I didn’t say it. Getting my mum to do something she disliked was a delicate process.

“So, mum, how did the phone call go?” I said with a mouthful of sandwich.

There was a short silence. I munched on my sandwich and imagined the various answers that might come.

“No one has claimed the bear, and I told the lady about your interest, and she said that if no one comes forward, you can have the bear and that you have to give it a good home. She said she thought the bear had been through a lot and needed a good, loving home. I’m pretty sure there were tears in her words,” said my mother, and there was a quiver in her voice.

This was not one of the answers I’d been expecting.

Days went by, and my mother made the call.

The bear was unclaimed.

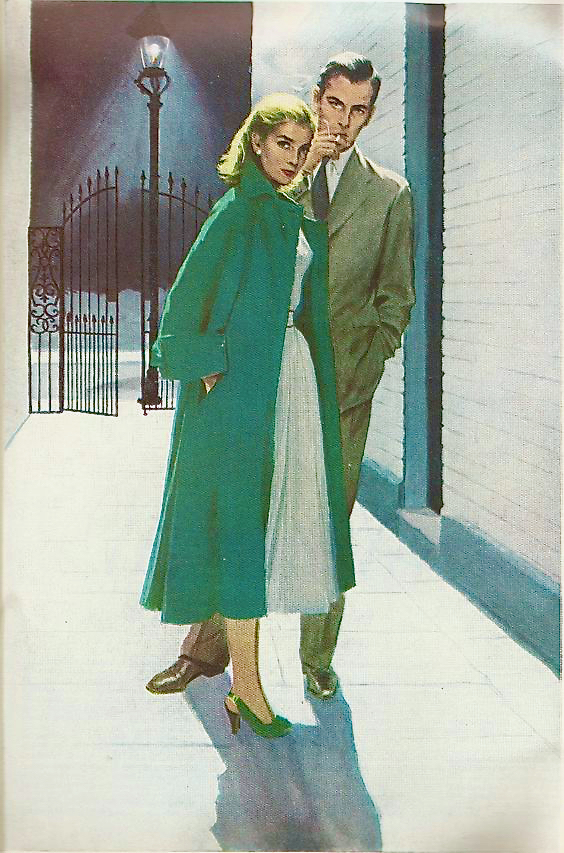

I dressed as you should when adopting a Teddy Bear, and my mother drove me to meet the lady and her rescue.

We drank tea out of beautiful cups, and my mother made small talk while I held the bear.

When we left her house, the lady looked sad, and I wondered why she didn’t want to keep the bear. After all, she was the one who found it.

The bear sat next to me in the car on the way home, and I put my hand on it so it would not fall when Mum put on the brakes. Dad says that Mum loves the breaks and will use them at any moment.

When I sat the bear next to my bear, I knew that she was only going to be mine for a short while.

I was going to be a foster parent. She would stay with me, but she was meant for you.

I hope you love and care for her the way that she deserves.

She must have been frightened sitting alone on that bus stop bench.

With you, she will have a home and someone to love.

.

.

.

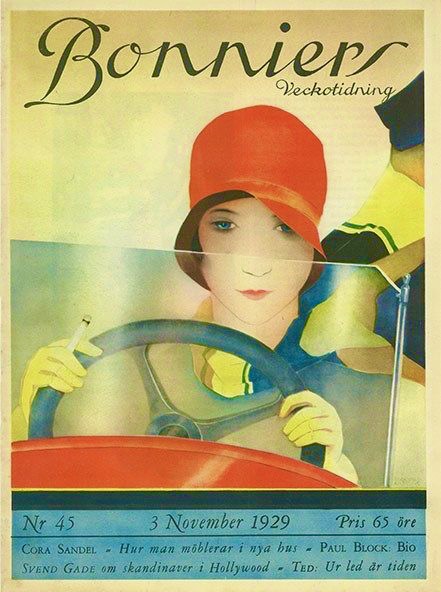

Painting:

You must be logged in to post a comment.